Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance, and Belonging. London: Reaktion Books and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Asuman Suner, New Turkish Cinema: Belonging, Identity, and Memory. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2010.

Deniz Bayrakdar, Aslı Kotaman, and Ahu Samav Uğursoy, editors, Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and the New Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009.

[Part One of this review essay, which considers Gönül Dönmez-Colin`s Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance, and Belonging, can be found here.]

Asuman Suner’s New Turkish Cinema: Belonging, Identity, and Memory may be in many ways the perfect complement to Gönül Dönmez-Colin’s book. Suner, who teaches at Istanbul Technical University, has written widely about contemporary Turkish cinema and, as she notes, an earlier version of New Turkish Cinema was published by Metis Press in Istanbul in 2006 (she refers to the present volume as “more of a reminiscence of the original volume than its repetition, for it includes extensive revisions”). Suner’s great strength is precisely as a reader of individual films; certain of her readings stand out almost as set pieces, illuminating the films in new and unexpected ways. Suner’s analyses of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Mayıs Sıkıntısı [Clouds of May] and Zeki Demirkurbuz’s Üçüncü Sayfa [The Third Page], both released in 1999, are particularly beautiful instances, as is her fine reading of Derviş Zaim’s 1996 film Tabutta Rövaşata [Somersault in the Coffin], a film that she considers one of the founding films of the New Turkish Cinema and a prime example of what she calls “new Istanbul films” that break with the romantic imagery of Yeşilçam in favor of “harsh and disturbing” imagery and a general mood that “can best be described as agoraphobic.”

Comparing their respective takes on particular films, Dönmez-Colin often displays the slightly superficial tone of a reviewer (in fact, one of her footnotes as part of her analysis of Tabutta Rövaşata cites a decade-old review of the film that she wrote for a cinema magazine), while Suner is more likely to dwell upon individual shots and sequences, and to focus on questions of form, style, and mood. She is attentive to literary influences in the films she addresses, noting, for example, the difference between the Chekhovian influences displayed in Ceylan’s work versus the more Dostoyevskian worldview portrayed by Demirkubuz. Suner is also more given to psychoanalytic and philosophical intertexts than to the more sociological and historical context provided by Dönmez-Colin—the Freudian notion of unheimlich is central to Suner’s analysis, although she is also quite concerned with the social and political context of the New Turkish Cinema.

[Still image from Derviş Zaim’s Tabutta Rövaşata (Somersault in the Coffin)]

As its title suggests, New Turkish Cinema focuses largely on the emergence of a new wave of filmmakers since the 1990s. Suner does provide a very brief historical perspective in her introduction, but it feels perfunctory, and it is clear that her real interest is in contemporary films. The difference in her approach, as compared to Dönmez-Colin, is clear from the opening examples each chooses: Dönmez-Colin starts with a classic Yeşilçam film and the figure of Türkan Şoray learning to be a star; Suner starts with a scene from Uğur Yücel’s 2004 film Yazı Tura [Toss Up], presenting us with the vision of a wounded veteran, recently returned to his hometown of Göreme, drifting through the streets and declaring “There are ghosts in these houses.” Suner suggests that this line “express[es] the central problem of the new wave Turkish cinema that emerged during the second half of the 1990s,” and she wastes no time in introducing us to the theme that will provide her book with its central focus: “New wave Turkish films, popular and art films alike, revolve around the figure of a ‘spectral home.’ Again and again they return to the idea of home/homeland; they reveal tensions, anxieties, and dilemmas around the questions of belonging, identity, and memory in contemporary Turkish society.”

Suner hews very closely to this set of themes throughout the whole of New Turkish Cinema. The book is organized not so much thematically as categorically, as Suner divides up the new wave of Turkish cinema into three primary headings: popular nostalgia films, new political films, and new Istanbul films. Sandwiched between these are two chapters simply entitled “The Cinema of Nuri Bilge Ceylan” and “The Cinema of Zeki Demirkubuz”; they are the two longest chapters, and contain the richest sets of readings and analyses. Suner’s final chapter, “The Absent Women of New Turkish Cinema,” is by far the shortest in the book, and it feels, like her introduction, a bit perfunctory. So does its central argument, which suggests that the general absence of women—or, more accurately, the absence of female characters who are active subjects rather than objects of male desire—“is one of the defining characteristics of new wave cinema.” At the same time, Suner argues, this fact “should not necessarily be considered an altogether negative condition,” since these films “sometimes include a critical self-awareness of their own complicity with patriarchal culture.” This is an interesting point, and it deserves to be fleshed out in much more detail; as it is, Suner’s handling of issues of gender and sexuality leaves something to be desired, especially when compared with Dönmez-Colin’s much more extensive analysis. Hopefully, Suner will have the chance to return to this argument regarding the ability of the new-wave cinema of Turkey to present this critical self-awareness regarding patriarchal culture.

Suner’s focus on the figure of the “spectral home” serves her particularly well in her analysis of what she calls “popular nostalgia films.” Focusing on popular films such as Serdar Akar’s Dar Alanda Kısa Paslaşmalar [Offside] (1999), Yılmaz Erdoğan’s Vizontele (2001), and Çağan Irmak’s Babam ve Oğlum [My Father and My Son] (2005)—all of which proved to be extremely popular and profitable films in Turkey—Suner does a fine job of examining how such films present a nostalgic view of the past. To do so, she draws on Gaston Bachelard’s notion of the “felicitous space” that comes into existence through our imaginative re-production of the childhood home as a space of protection, intimacy, and well-being (whatever the actual reality of our childhood might have been). In Suner’s account, recent popular nostalgia films present the recent past “transformed into an image of the felicitous space of childhood.”

This is a particularly interesting point, since these films contradict the frequently-made accusation that Turkish society is simply an amnesiac society that wishes to completely ignore or forget the past. These films do engage with the past, and do not shrink from representing political events from this past, such as the 1980 military coup and its aftermath; indeed, as Suner notes, through their frequent representation of the central government’s tendency to intervene in local community matters, nostalgia films often “engage in a subtle critique of state authority in Turkey.” However, she concludes, their failure to produce “an objective account of the past” and their reliance upon “subjective accounts of memory shaped around a strong sense of nostalgia” prevent them from becoming full-fledged “historical films.” This distinction between “subjective” and “objective” historical accounts is a bit of a dicey proposition, but it does provide Suner with a powerful framework for the analysis of the films she considers.

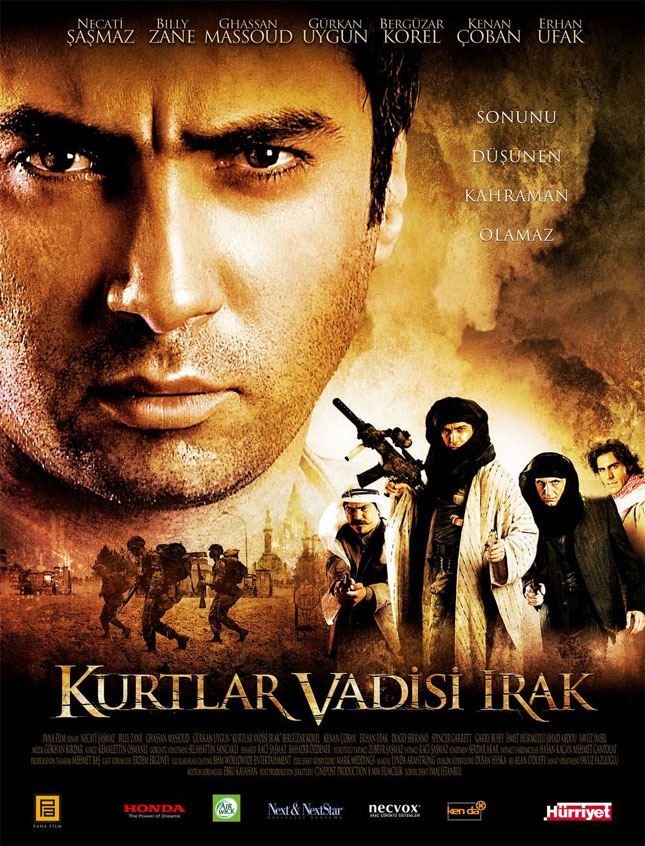

Particularly fascinating in this respect is her reading of Serdar Akar’s blockbuster Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak [Valley of the Wolves: Iraq] (2006), which became the top-grossing film in Turkish cinema history (and which in 2011 spawned a sequel, Kurtlar Vadisi: Filistin [Valley of the Wolves: Palestine]). Set in northern Iraq, the film is based loosely upon the actual detention and deportation of a group of Turkish soldiers stationed in Iraq by US forces in July 2003. Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak presents this incident, in which the Turkish soldiers were hooded by US troops, alongside a wide array of documented atrocities committed by US forces in Iraq; it was, for example, the first fictional film to represent the actions of US forces at Abu Ghraib prison. While the film clearly draws upon the outrage felt throughout Turkish society (and, indeed, throughout the world) regarding the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, Suner argues that the film’s critical position towards the invasion “is grounded not in a historically informed understanding of politics, but in a transhistorical plot based on a Manichaean battle of good and evil.” Furthermore, Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak shares with other contemporary films a nostalgic relationship to the past, since through its claim that the Ottoman empire represented a benign force in the region (especially compared to the Anglo-American invaders who followed), the film represents “precisely what contemporary Turkish nationalism is nostalgic about: the long-lost Ottoman/Turkish imperial power.” “Drawing upon a romantic fantasy of belonging,” Suner concludes, at the end of her chapter, “popular nostalgia films cannot handle . . . a facing up to the past. This challenging task is taken up by new political films.”

[Poster for Serdar Akar’s Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak (Valley of the Wolves: Iraq). Image from Google Images.]

This distinction between “nostalgia” films and “political” films provides Suner with a powerful analytic and categorical framework, and for making a critical distinction between the “popular” films she analyzes in the first chapter and the “arthouse” films of Ustaoğlu, Zaim, and Yücel. That said, the line she draws risks a fall into a sort of critical glibness. Reading Suner’s distinction between nostalgic and political films, I was reminded of Godard’s observation that if a worker buys a camera and films his vacation, what he creates is by its nature a political film, since it represents the limitations under which it is produced (he notes that the same worker would not be allowed to film his own workplace or the house of his boss—it should of course be remembered that Godard made this point before the age of camera phones and YouTube). In other words, it is debatable whether the only political reading of a film consists in an analysis of the politics contained within the film itself, or rather whether it might not also be worth considering the way that popular nostalgia films represent a situation in which political responses are by their very nature limited.

In considering the unmistakably conspiratorial tone of a film such as Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak, for example, it would be interesting to draw on the recent work of Slavoj Žižek, which suggests that conspiracy narratives might be understood in part as ultimately insufficient and reactionary attempts to come to terms with the paranoiac nature of the contemporary world and with the ultimate (and horrifying) illogic of historical actions such as the invasion of Iraq—or, for that matter, Fredric Jameson’s earlier claim that “conspiracy theory” films are often attempts to comprehend the greatest “conspiracy against the public” of all: global capitalism itself. This is certainly not to deny the deeply reactionary nature of a film such as Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak or to suggest that such a film be read sympathetically; it is simply a way of suggesting that one aspect of a politically-grounded criticism might be to work to pull out and illuminate the utopian shards (as Ernst Bloch would say) that might be embedded in even these sorts of films, rather than simply moving on to analyze films with “better” politics. All this said, Suner shows herself to be a perceptive reader of all the films in question, and her conclusion regarding the “new political films” of Ustaoğlu, Zaim, and Yücel—the insight that they deal with the traumatic nature of Turkey’s historical past and, in the process, challenge not just the nature of “national cinema” but also “the very notion of ‘Turkish cinema’ as a classificatory designation”—is a crucial, and quite well-argued, point.

In general, Suner’s reliance upon analyzing the centrality of “the spectral home” in the New Turkish Cinema serves her well. This framework, for example, works for her analysis of Ceylan’s films, where she reads out the centrality of a certain notion of “play” in his cinema. It also works well as part of her brilliant analysis of what she calls “new Istanbul films,” including her fine readings of Fatih Akın’s films Gegen die Wand [Head-On] (2004) and Crossing the Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul (2005). While, as she notes, Akın’s identity as a Turkish German director problematizes his relationship to the New Turkish Cinema, the outside-in perspective of these two films is actually very much in line with other new Istanbul films, which collectively cast a fresh eye over the city in order to break away from the clichés of the Yeşilçam era (Akın’s satirical use of musical interludes set against the backdrop of the Golden Horn and the Süleymaniye Mosque in Gegen die Wand is a particular dramatic example).

[Still image from Fatih Akın’s Gegen die Wand (Head-On)]

Suner’s “spectral home” framework proves somewhat less apt, however, for her analysis of Demirkubuz’s films: she does a nice job of reflecting the spaces of claustrophobic domesticity found in his films, but she neglects the other major element: his brilliant representation of the suffocating blandness of the bureaucratic spaces that his characters are continually made to occupy. This portrayal of the interpenetration of the domestic and the bureaucratic in modern life, and the extent to which the two spaces have come to resemble each other (so that, for example, when a Demirkubuz character leaves prison and returns home, the two spaces seem terrifyingly similar), is something Demirkubuz shares with both his major literary influence, Dostoyevsky, and one of his major cinematic influences, Krzysztof Kieslowski. By focusing largely on the domestic spaces in her otherwise quite perceptive readings of Dermirkubuz’s films, Suner by and large neglects this important aspect of his films.

It needs to be said that the perhaps inevitable downside to Suner’s finely tuned focus upon individual films and auteurs is a corresponding weakness in some of her larger-scale observations. In fact, when she turns to the broader picture, some of her attempts to provide historical context are so general as to approach total banality: “The 1990s were an ambivalent decade for Turkey, leading to bleak events in society along with some promising developments,” or “Over the last two decades, memory has become a major cultural obsession across the globe.” But just as Dönmez-Colin’s strengths as a chronicler of overarching issues in Turkish cinema outweigh her weakness as a reader of individual films, so does Suner’s great talent as a reader of cinematic texts outweigh her weakness as a film historian (which, in fairness, she never claims to be). In its strongest moments, New Turkish Cinema exemplifies all that is best in contemporary cinema studies. One regrets the vicissitudes of academic publishing, with the long gaps of time between the writing of a book and its publication: a number of recent films, including Ceylan’s Üç Maymun, Akın’s Auf der anderen Seite [The Edge of Heaven], and Demirkubuz’s Kıskanmak [Envy], seem tailor-made for the critical approach that Suner brings to bear in her book (she has, however, recently written on Semih Kaplanoğlu’s Bal [Honey], which won the Golden Bear at the 2010 Venice Film Festival, and Özkan Alper’s 2008 debut Sonbahar [Autumn]).

[Still Image from Zeki Demirkubuz’s Yazgı (Fate)]

The third book under review here, the edited collection Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and the New Europe, is, like many essay collections, something of a mixed bag. Cinema and Politics brings together a series of papers that were presented at a conference of the same name at Kadir Has University in Istanbul in 2007. The structure of the book is a bit baffling: it begins by reprinting Ella Shohat’s essay “Sacred Word, Profane Image: Theologies of Adaptation,” originally published in 2004. Shohat’s essay remains a fresh and original analysis, but it is hard to see the connection between this piece and the essays that follow. There follows a section with the title “European Cinema: Politics of Past and Present,” featuring essays on Pasolini, Ken Loach, and Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari; the most interesting piece in the section is Elif Akçalı’s essay on Lars von Trier’s Dogville and Manderlay. Again, while these are all fine essays, it is unclear how they relate to the topic of “Turkish cinema and the new Europe.” A stronger editorial framework might have succeeded in bringing together these disparate elements, but the book as a whole suffers from a general sense of disjointedness. It is perhaps notable in this respect that Deniz Bayrakdar, who is credited as the volume’s main editor, contributes two of the most fractured and least coherent pieces to the volume: an introduction with the odd title “‘Son of Turks’ Claim ‘I’m a Child of European Cinema,’” which fails to provide much of a framework for the sections that follow, and an essay, ostensibly on Akın’s Auf der anderen Seite, which is more an anecdotal account of some of the author’s general thoughts on New Turkish Cinema than an actual analysis of Akın’s film.

However, a reader who is not put off by the organizational challenges offered by Cinema and Politics will be rewarded with a number of insightful essays that provide thoughtful complements to the work done in Dönmez-Colin’s and Suner’s books. These include Levent Soysal’s fine chapter, from a section of the collection dealing with migration films, which intriguingly brings together Tunç Okan’s 1974 film Otobüs and Akın’s Gegen die Wand with Pedro Almadovar’s early film ¿Que he hecho para merecer esto? [What Have I Done to Deserve This?] (1984); it seems an unlikely combination, but Soysal makes it work, and it leads to a very interesting comparative perspective. Nevena Dakoviç’s chapter on Serbian cinema and its relationship to the process of Serbia’s integration into the European Union also provides an interesting intertext to the way the cinema of Turkey has dealt with Turkey’s vexed relationship to the European Union.

The last four sections of the book all deal with the New Turkish Cinema, and it is these sections that provide the most interesting analyses. Yılmaz Güney emerges again as a key figure in this collection. Murat Akser provides a fascinating analysis of the films that Güney made during the earliest part of his career as an actor, specializing in action films where he played, as Akser puts it, “beautiful losers” (Akser makes an interesting parallel between Güney and John Cassavetes, another actor who parlayed his success in popular films into a career as a director of revolutionary independent cinema). Eylem Kaftan offers a fine reading of Güney’s influential films Sürü [The Herd] (1978) and Yol [The Way] (1981). Reading Kaftan’s essay alongside the other two books, I was struck by how strongly the two major tropes that Güney deploys in Yol—the journey that reveals the suppressed stories to be found in every corner of the nation, and the prison as a metaphor for the political condition of Turkish society more generally—proliferate throughout the large body of work that represents the New Turkish Cinema. Zeynep Koçer’s analysis of Halit Refiğ’s 1964 film Gurbet Kuşları [Birds of Exile] also does a fine job of elucidating some of these political issues that motivated the work of the “new” filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s and that continue to exercise the imaginations of the “new new” wave of filmmakers of the past two decades.

[Still image from Yılmaz Güney`s Yol (The Way)]

A section of the book devoted to the politics of nationalism in contemporary Turkish cinema is anchored by a strong essay by Kaya Özkaracalar. Focusing on Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak, Özkaracalar stresses that the film’s critique of American imperialism is ultimately “brought to the screen not with anti-imperialist but with nationalistic motives.” Özkaracalar provides an interesting context for this analysis by comparing Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak with two earlier films that engaged with American imperialism: Melih Gülgen’s Cemil (1975), a film that, like Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak, funnels its anti-American-imperialism sentiments into a chauvinistic nationalist discourse, and Ertem Göreç’s Karanlıkta Uyananlar [Those Who Wake Up in the Dark] (1964), which, by contrast, represents imperialism “not as a military force but as a force of capital” and, through the process of its representation of the struggles of workers at a paint factory, presents itself as an alternative road not yet taken by contemporary Turkish films. Müberra Yüksel and Hande Yedidal contribute essays on the role of film as a mediator of conflicts and upon the representation of “invincible Turk” figures adapted from comic strips for contemporary films, respectively; while both essays provide some interesting insights, neither essay ever quite coalesces into a coherent whole.

A section of the book that focuses on the “politics of ephemeral identities” displays some of the general unevenness of the volume as a whole. It features Zahit Atam’s very valuable reflections on the origins of the New Turkish Cinema, with a particular focus on the political and cultural effects of the 1980 military coup and the dark period of repression that followed. Atam, like Suner, notes the influence of nostalgia in popular films, and the countervailing tendency of new wave films to focus upon “anxious, unhappy, stressful, broken lives.” He goes a bit beyond Suner, however, in attributing both tendencies to an accurate reflection of what he sees as the wounded and insecure nature of Turkish society as it recovered from this dark and violent historical period. In his very moving reading of Demirkubuz’s films in this context, Atam finds not just the Dostoyevskian elements noted by Dönmez-Colin and Suner, but also a strong trace of Beckett, particularly in the lines that Demirkubuz adapts in the final scene of his film Masumiyet [Innocence] (1997): “You always tried. You always lost. Let it be. Try again. Lose again. Be a better loser.” Atam suggests that these words “in a sense became the launching words of the New Turkish Cinema.” Atam’s fine essay is followed, however, by Zeynep Tül Akbal Süalp’s rather baffling look at the same historical period, which contains moments of great potential interest (for example, a very suggestive comparison between Demirkubuz and Michael Haneke) that are left undeveloped. And Süalp’s essay is followed in turn by Aslı Kotaman’s brief but intensely focused reading of Demirkubuz’s films Yazgı [Fate] (2001) and Kader [Destiny] (2006), which gives a nice sense of Dermirkubuz’s critical reflections on the nature of “freedom” (or lack thereof) in contemporary Turkish society.

In the book’s final section, Özlem Avcı and Berna Uçarol Kılınç provide a useful overview of changing representations of Islamic ways of life in Turkish cinema since the 1980s. The book closes with two very strong essays. Savaş Arslan considers versions of masochism in a series of contemporary films. Following Deleuze, he defines masochism as “a contract between two parties, in which the supposed victim is giving the orders”; Arslan finds this to be a convenient schema for analyzing what he calls “male weepies” that focus on the feelings of loss experienced by male characters, among them Yavuz Turgul’s Eşkıya [The Bandit] (1996), Ceylan’s İklimler [Climates] (2006), Demirkubuz’s İtiraf [Confession] (2001), Çağan Irmak’s Mustafa Hakkında Herşey [Everything About Mustafa] (2004), and Yücel’s Yazı Tura [Toss Up] (2004). In a sense, Arslan provides a continuation of Suner’s not-fully-developed argument about the question of masculinist identities in the New Turkish Cinema, providing a convincing case that such films have begun to address “the group fantasy to which state violence owes itself” (Arslan’s book Cinema in Turkey: A New Critical History, recently published by Oxford University Press, represents another important contribution to the development of Turkish cinema studies in English, although it is unfortunately beyond the bounds of this review). In the final chapter of the book, Övgü Gökçe provides an extraordinary reading of Ustaoğlu’s Bulutları Beklerken [Waiting for the Clouds] (2003) and Özkan Alper’s Sonbahar [Autumn] (2008). The aesthetic approach of both films, Gökçe argues, “marks an exceptional point in Turkish cinema in terms of trying to find a way of speech to articulate loss.” While she notes the political aspects of the stories represented by both films, she also does a beautiful job of reminding us that this political intervention comes precisely through the aesthetic interventions of the films; in the process, both films make us newly aware of the nature of film “as a practice of remembrance or mourning” and also remind us of “the difficulty to remember or mourn.” Films such as Bulutları Beklerken and Sonbahar, Gökçe concludes, “signify a crucial point for the beginnings of a possibility in Turkish cinema.”

[Still image from Özkan Alper’s Sonbahar (Autumn)]

It is just as well to end on this note of possibility. The points of disagreement and disconnect between these three books, and even the sense of unevenness among the contributions to Cinema and Politics, should leave us optimistic about the state of the field of Turkish cinema studies in English. All three books serve as useful points of entry for readers new to the cinema of Turkey; all three also point to areas in need of further explanation and analysis. While many of us are drawn to the “lonely and beautiful” vision of Ceylan and his contemporaries, it may be that the cinema of Turkey is about to become a lot less lonely.

Filmography

At, Avrat, Silah [Horse, Woman, Gun]. 1966. Dir. Yılmaz Güney. Kazankaya Films.

Auf der anderen Seite [The Edge of Heaven]. 2007. Dir. Fatih Akın. Anka Film.

Bulutları Beklerken [Waiting for the Clouds]. Dir. Yeşim Ustaoğlu. Ustaoğlu Filmcilik.

Cemil. 1975. Dir. Melih Gülgen. Gülgen Film.

Dar Alanda Kısa Paslaşmalar [Offside]. 2000. Dir. Serdar Akar. Umut Sanat.

Gegen die Wand [Head On]. 2003. Dir. Fatih Akın. Bavaria Film International.

Güneşe Yolculuk [Journey to the Sun]. 1999. Dir. Yeşim Ustaoğlu. IFR.

Gurbet Kuşlari [Birds of Exile]. 1964. Dir. Halit Refiğ. Artist Film.

Hudutlarin Kanunu [The Law of the Borders]. 1966. Dir. Lütfi Ö. Akad. Dadaş Film.

İklimler [Climates]. 2006. Dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Pyramide.

Kader [Destiny]. 2006. Dir. Zeki Demirkubuz. Mavi Film.

Kara Gözlüm [My Dark-Eyed One]. 1970. Dir. Atıf Yılmaz. Akün Film.

Karanlıkta Uyananlar [Those Who Wake Up in the Dark]. 1964. Dir. Ertem Göreç. Filmo Ltd.

Kurtlar Vadisi: Irak [Valley of the Wolves: Iraq]. 2006. Dir. Serdar Akar. Pana Film.

Masumiyet [Innocence]. 1997. Dir. Zeki Demirkubuz. Mavi Film.

Otobüs [The Bus]. 1974. Dir. Tunç Okan. Pan Film.

Sonbahar [Autumn]. 2008. Dir. Özkan Alper. Filmfabrik.

Sürü [The Herd]. 1978. Dir. Yılmaz Güney. Güney Film.

Susuz Yaz [A Dry Summer]. 1963. Dir. Metin Erksan. Hitit Film.

Tabutta Rövaşata [Somersault in the Coffin]. 1996. Dir. Derviş Zaim. IFR.

Üç Maymun [Three Monkeys]. 2008. Dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan. Zeyno Films.

Umut [Hope]. 1970. Dir. Yılmaz Güney. Lale Film.

Uzak [Distant]. 2002. Dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan. NBC Film.

Yazgı [Fate]. 2001. Dir. Zeki Demirkubuz. Mavi Film.

Yazı Tura [Toss Up]. 2004. Dir. Uğur Yücel. Cinegram.

Yol [The Way]. 1981. Dir. Yılmaz Güney. Güney Film.